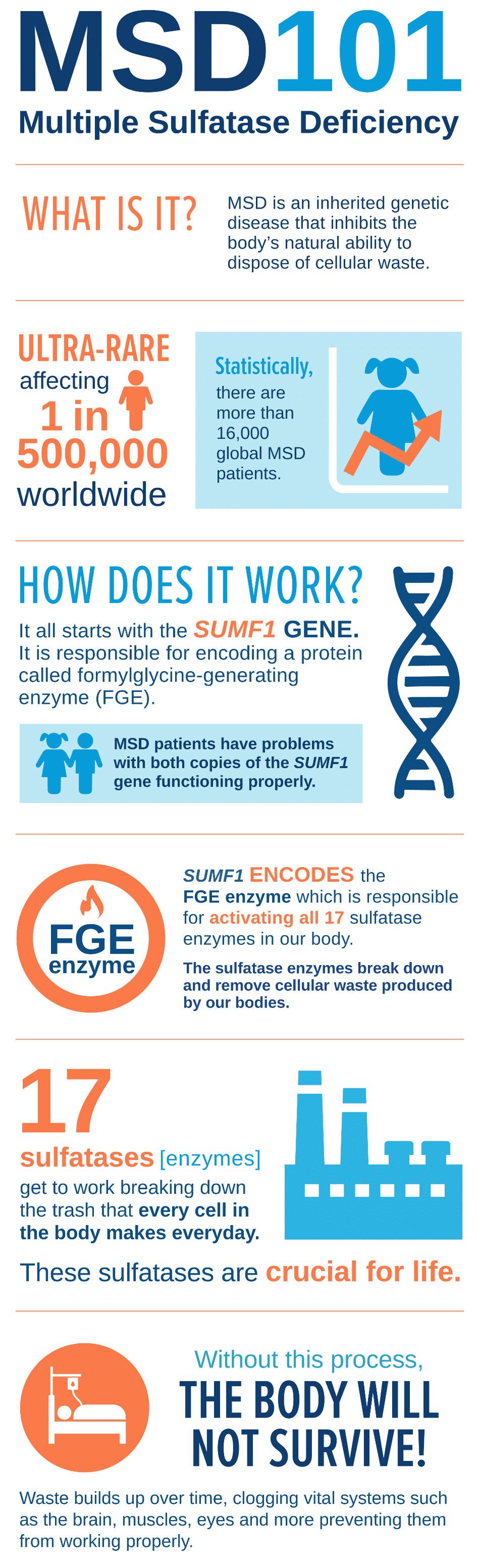

What is MSD?

MSD is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease caused by the build-up of cellular waste throughout the body and leading to regression of every body system. The average life expectancy for a child with MSD is 13 years of age.

Ultra-rare Disease

MSD is a lysosomal storage disease, meaning the body does not break down and filter out the natural cellular waste that occurs in everyday cell functions. Children are typically without any symptoms at birth, but depending on their specific genetic variants, signs of MSD can begin either soon after children are born or later on in the child’s life.

Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency can vary in severity, with more severe cases presenting earlier in life and progressing more quickly and with attenuated forms presenting later in life and progressing more slowly. It is important to remember that every child with MSD is unique and will follow their own path.

Historically, MSD has been presented as having three subtypes: Neonatal, Late-infantile, and Juvenile. The neonatal form is the most severe and can present in utero or at birth. These children decline very rapidly and often die during the first two years of life. Late-infantile is the most common form. Children with this form have normal cognitive development at the beginning of life but gradually begin to regress and lose skills. The final form, Juvenile, is the rarest. Individuals with this form typically do not show signs or symptoms until middle to late childhood and, generally, they have a slower loss of skills.

What Causes MSD?

In each cell of our body, there is a substance called DNA which contains the instructions for our growth, development, features, and health. When an embryo is formed in the womb, half of its genetic information originates from the egg and half from the sperm. This means that all individuals have two copies of their genetic information. Within our DNA, there are specific sections called genes that code for proteins that, in turn, carry out numerous functions in our body.

SUMF1 Gene – Why We Need It

Individuals with MSD are born with both copies of their SUMF1 gene not functioning properly. This gene is important as it codes for a protein called formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE), which is responsible for turning on a class of proteins called sulfatases. For individuals with MSD, the harmful changes in both copies of their SUMF1 gene lead to reduced or absent amounts of FGE resulting in inactive sulfatases. This is why the condition is called Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency because individuals with MSD are unable to activate their sulfatases, causing them to appear deficient on tests.

MSD is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, meaning that both copies of the SUMF1 gene must have harmful changes to cause symptoms. Individuals with MSD typically receive one non-working copy of the SUMF1 gene from their biological mother and another non-working copy from their biological father. The parents of a child with MSD are considered to be “carriers” as they have one working and one non-working copy of SUMF1 and will not develop signs/symptoms. It is important that parents undergo genetic testing to confirm that they are carriers of the same harmful changes identified in the child. This is also helpful when considering future family planning options.

Early Signs of MSD

Most children with Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency appear healthy at birth and typically do not show any obvious signs or symptoms of the disease. However, some severe cases of MSD can have features present in the womb or at the time of birth.

Every child with MSD is unique, and no one knows your child like you do. You are aware of their every move, mannerisms, and habits. You see their eating habits and communication skills. As a parent or caregiver, you may start to notice small changes in your child’s development or behavior. Failure to meet certain developmental milestones, in combination with other displayed symptoms, could be a sign that something is wrong.

Early Features of MSD

- Increased muscle tone

- Recurrent ear and/or sinus infections

- Difficulty balancing

- Difficulty eating and/or swallowing

- Poor sleep

- Seizures

- Autistic features/Coarse facial features

- Long and full eyelashes and eyebrows

- Dry skin across their bodies

- Loss of neurological function

- Loss of speech or taking longer to achieve developmental milestones

- Loss of motor skills

(ability to walk, sit up, etc.)

Other features such as an enlarged liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly), progressive skeletal dysplasia (dysostosis multiplex), buildup of fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus), and intestinal hernias can occur in children with MSD.

As the disease progresses, these symptoms will worsen and your child will eventually need constant full-time care.

How MSD is Diagnosed

When diagnosing MSD, there are two categories of testing: Biochemical and Molecular/Genetic. Individuals with MSD should ensure that they have undergone both Biochemical and Genetic Testing to confirm their diagnosis. If you are interested in meeting with a genetic counselor, who can organize genetic testing, connect you with resources, and help coordinate care, you can search for a local genetic counselor in your area. The United MSD Foundation has created a physician guide to help start the conversation with your child’s doctor.

Biochemical Testing

There are a number of biochemical tests that can be run if a healthcare provider is suspicious of MSD. A blood and/or urine sample is often taken from the patient and various enzyme and metabolite levels are measured. Some of these levels include measuring the sulfatase activity and the quantity of waste materials (glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), sulfate levels, sulfatides, etc.). It is important to note that not every child with MSD will have elevated GAG levels, but this does not mean that they do not have MSD.

Molecular/Genetic Testing

Providers will also likely order genetic testing to examine the SUMF1 gene. Similarly, a sample, usually blood or saliva, will be taken from the patient and sent to a diagnostic laboratory. At the lab, the SUMF1 gene will be closely analyzed to see if there are any genetic differences (variants) compared to the reference genome. If the laboratory notices a difference, they will check to see if the genetic difference has an effect on the function of the gene. If an individual is found to have a harmful genetic difference on both copies of their SUMF1 gene, then they would receive a genetic diagnosis of MSD. A geneticist or genetic counselor can help facilitate the ordering and interpretation of genetic testing.

For individuals with signs and symptoms consistent with MSD,

Invitae is currently running a program to provide free genetic testing.

Learn More About Free Testing

Learn More About Free Testing

Let’s Connect

Connect with MSD families and get valuable information from medical researchers and doctors.